Download the Report

Executive Summary

China is accelerating dam building on the upper reaches of the Machu or Yellow River despite evidence from Chinese scientists of the risks of geological disasters and serious environmental problems.

China’s heavy infrastructure construction upriver on the plateau, closer to the previously redlined ecological zone and the melting glaciers of Tibet’s Amnye Machen range, risks releasing more methane into the atmosphere as permafrost thaws and degrades further. Entire villages are being displaced and ancient monasteries submerged to make way for the construction of dams by the same state-owned corporations that are building more coal-fired power stations in China, the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases.

This report reveals new information on the construction of hydropower dams high upstream on the Machu/Yellow River, documenting:

- For the first time, China’s construction of hydropower dams is reaching upstream to the sources of Asia’s great wild rivers in Tibet, with at least three major new dams on the upper Machu (Chinese: Huang He) river. Chinese scientists have warned of the risks of heavy infrastructure construction in a seismically unstable region where river systems are increasingly unpredictable due to climate change.

- Outside the Arctic, Tibet’s permafrost zone is the largest in the world. But construction of dams at such high altitudes means building on permafrost, which may thaw each summer, then freeze again in winter, creating unstable subsoil risking the stability of the dam itself. As the permafrost in the soil of 1.6 million square kilometres of the Tibetan plateau melts, methane stored in the soil or generated by microbial digestion of formerly frozen vegetation is released into the air. This is much more potent than carbon dioxide as a heater of the atmosphere. There is no indication that China has policies or plans to prevent the methane gas emissions rising as permafrost thaws.

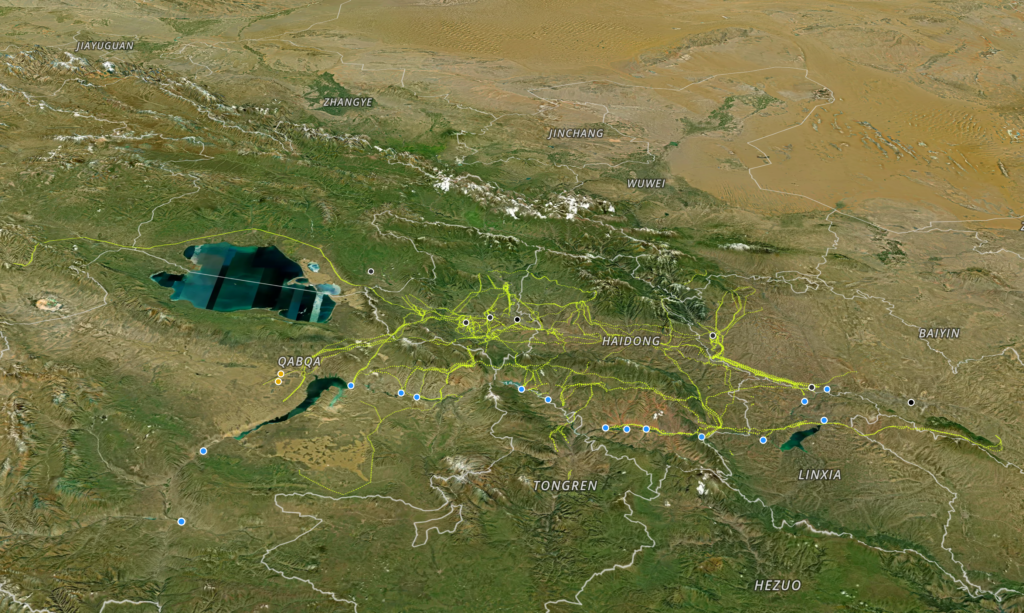

- A 3D map provided with this report illustrates a region in Tibet where renewables coexist with coal infrastructure. While China can point to its solar and hydro projects in Tibet to signal a green transition, the smart grid is currently orientated to fossil fuels, which may reveal a slower, less substantial shift than these projects imply. Although hydroelectric power is technically renewable, the large-scale hydropower projects underway in Tibet have complex environmental and social impacts, including ecosystem disruption and displacement of communities.

- The first major dam to be built upriver on the Machu, the Yangkhil (Yangqu) hydropower station, has devastated an entire community. Accounts and images from eyewitnesses in this report documents how Tibetans have been compelled to dismantle their own homes and an important monastery has been emptied and destroyed. China removed the monastery from a protected heritage list before beginning demolition to make way for a dam that Chinese engineers boast is constructed by AI-driven robots.

- High on the Machu, in the deep waters of the massive reservoir behind the Longyangxia dam, China has initiated mass production of factory-farmed fish for consumption in China, a practice that is abhorrent to Tibetans. Rainbow trout, which are alien to Tibet, are bred and slaughtered by the millions every year and marketed to Chinese consumers as salmon, which led to a scandal in China in 2018. This massive agribusiness, originally supported by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN, has been deemed so successful that another of the new dams further upriver, Bangduo, is being slated to produce even more trout. This has raised alarm among Chinese scientists of the impacts to the ecosystem of a possible escape of an invasive species.

- Already, a cascade of nine hydropower stations interrupts the Machu/Yellow River, which makes the Tibetan Plateau a major exporter of electricity by ultra high voltage power grid to distant inland province Henan, powering its intensifying industrialisation and rising carbon emissions. These dams exploit the kinetic energy of a river that – far downstream – is celebrated as a cradle of Han Chinese civilisation. In the provincial capital of Qinghai, Xining, in June, Xi Jinping equated ‘Yellow River culture’ with China’s ‘Sinicisation’ drive that compels Tibetans to adopt a nationalist Chinese identity, culture and language, while seeking to erase their own distinct ways of life, livelihoods and Buddhist practices.

Tibetans risked their lives in February to protest the construction of the Kamtok (Chinese: Gangtuo) dam in the upper reaches of the Drichu/Yangtze. The dam threatens to submerge their homes and six monasteries with precious 14th century frescoes that Chinese scholars have also sought to protect. The courage of Derge Tibetans drew attention to the risks of a cascade of adverse consequences both on the plateau and downstream in China of dam building so high upstream. Hydro projects upstream in Tibet also impact farmers and fisherfolk down river in Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos and Myanmar.

But to Xi Jinping’s Politburo, water is a key strategic asset, and securitising the plateau and its water sources is of overriding concern. The Party state’s 2023 National Water Plan urges the strengthening of the ‘Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Chinese water tower protection’, but it also aims to make water a commodity that is traded and bought by agribusinesses and massive Chinese state owned corporations to power China’s development.

Turquoise Roof is also providing our readers with an interactive map of the region to accompany this report. We encourage the reader to explore the landscape in the impacted area while they read this report. This map illustrates a region in Tibet where renewables coexist with coal infrastructure. The concentration of the power grid around coal-fired plants shown in the map that accompanies this report indicates China’s continuing reliance on fossil fuels, which is contradictory to claims of aggressive decarbonization. Despite the visible presence of renewable energy sources, renewable sources do not appear to be as well integrated in the grid as fossil fuels. This reflects a gap between the country’s green energy claims and its actual operational practices.

Although hydroelectric power is technically renewable, large-scale hydropower projects have complex environmental and social impacts, including ecosystem disruption and displacement of communities, as demonstrated in this report. China’s strategic use of hydropower, alongside coal, might be intended to present a cleaner energy profile without addressing the deeper ecological consequences. The map is rendered with Mapbox GL JS v 3.2.0 and the application was coded by Paul Franz.